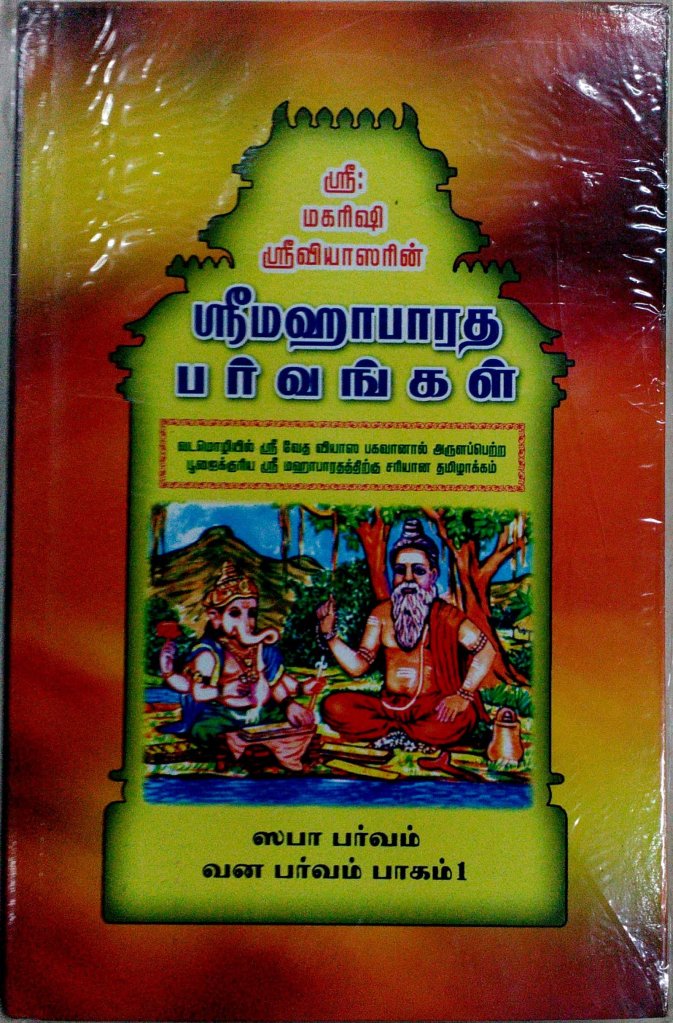

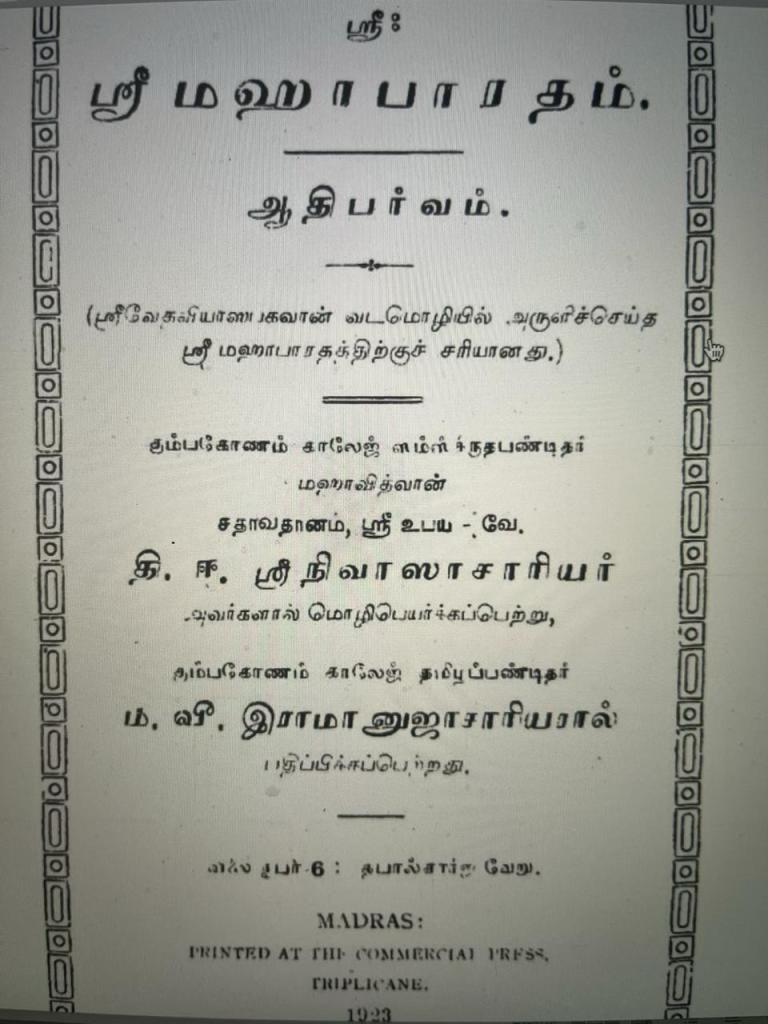

On this occasion of World Mother Language Day (21st February), it is apt to discuss the trials and tribulations of Mahāmahopādhyāya (the great teacher), Shri Manalur Veeravalli Ramanujacharya, and his tireless efforts to translate the original texts of the Sri Mahabharatam from Sanskrit to Tamil. As a teacher at Kumbakonam College, Sri Ramanujacharya, equipped with a deep knowledge of Sanskrit acquired in Kashi, sought to make the Mahabharatam accessible to Tamil readers.

This was during the colonial period, a time when such monumental endeavours required financial backing, either from wealthy patrons—primarily businessmen or local rulers—or through petitions to the colonial government. Over 25 years, Shri Ramanujacharya meticulously worked on this epic in a puritan manner, employing scribes, scholarly translators, and others to ensure a faithful and precise translation. However, (his financial struggles were well-documented) burdened by heavy debts and an inability to secure consistent sponsorship, he was forced to publish the translation in small, fragmented portions. Literary historians note that publishers of the time showed little interest in supporting his work, instead choosing to prioritize translations of the first English version of the Mahabharatam.

In stark contrast to this indifference towards enriching Tamil literature, there was a parallel literary movement occurring at the same time. Victorian pulp novels, particularly those by G.W.M. Reynolds, gained immense popularity among English-speaking Indians. These novels were not merely read but were shamelessly adapted into local languages, often without acknowledgment. The official rationale for flooding India with Reynolds’ novels was to popularize the novel form in India. While this might have been partially true, the result was the creation of an entire genre of translated Victorian pulp fiction, with themes designed to titillate readers rather than enrich indigenous literature.

Social historians have explored the impact of these novels on the literary development of colonial India, and it is interesting to note that opposition to them came from Indian nationalists across the country—though that is a discussion for another time.

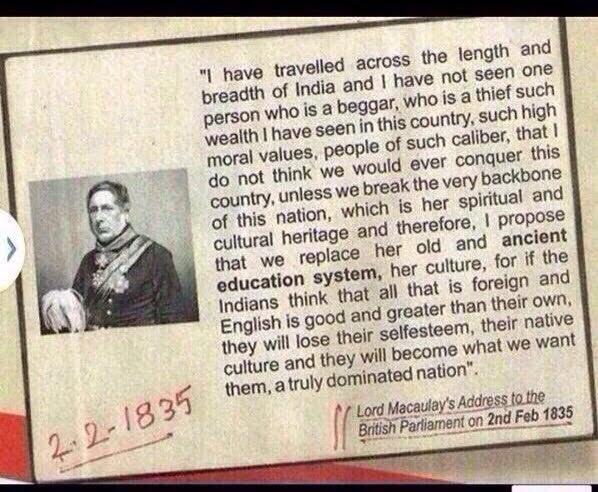

The purpose of this blog, in honor of World Mother Language Day, is to examine the historical journey of our indigenous languages. While Macaulay’s infamous 1835 policy is often held responsible for the marginalization of local tongues, and even though this very blog is written in English, it is essential to recognize that not all blame lies at Macaulay’s door. The responsibility to nurture and promote our mother tongues ultimately rests with us. It is not too late to contribute, in whatever small way we can, to the revival and popularization of our native languages.

Leave a comment